Strategic Planning in the Arts: A Practical Guide

Organizational Structure

| next |

The adage that structure should follow strategy applies to the organizational structure of an arts organization as well. Indeed, the last element of the strategy that should be developed is the way the staff should be organized to accomplish the proposed operating strategies.

If the structure is allowed to determine the strategy, as it does in many institutions, the organization can do little more than maintain its current status. In many instances, unless the structure is changed, the ability of the proposed strategies to create change is severely limited.

This does not mean that the current organization and staffing should be ignored when developing a strategic plan, nor that one has absolute flexibility in altering an organization structure. The institution's historical relationship to particular staff members, union requirements and other intangible factors will all affect the flexibility the planner has to alter the organizational structure. However, it is frequently true that as strategies are altered, the organizational structure, job descriptions and even personnel selected to fill important positions must change as well.

There is not one correct organizational structure. As dance companies mature, they typically have two leaders - one artistic and one administrative. The artistic leader of a dance company tends to spend so much time in the dance studio that it is essential to have a co-equal partner managing the company.

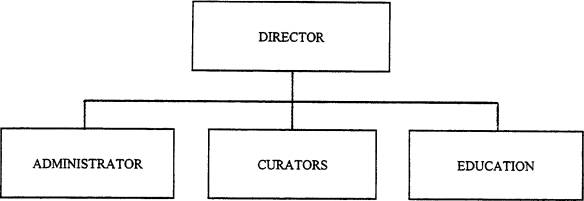

Symphony orchestras tend also to have two leaders although for major ensembles, the music director is frequently out of town on guest conducting assignments leaving the executive director with greater day-to-day authority than in a dance company. Traditionally, museums and opera companies have had one director who manages both the artistic and administrative sides of the organization, but who comes from an arts background. The director is usually supported by a strong administrator.

"TYPICAL" DANCE COMPANY ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE

• DANCERS |

|

• DEVELOPMENT |

• CHOREOGRAPHERS |

|

• MARKETING |

• DESIGNERS |

|

• FINANCE |

• TEACHERS |

|

|

"TYPICAL" MUSEUM ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE

• DEVELOPMENT

• MARKETING

• FINANCE

• OPERATIONS

As the level of sophistication required to market and support any large arts institution has increased, more organizations are experimenting with the model embraced by dance companies and symphony orchestras.

Yet many museum and opera company Board and staff members are skeptical that a dual leadership plan can be effective. They fear that the art will "take a back seat" to the financial status of the organization despite the fact that this structure has worked well in many dance companies, symphonies and theater companies, ensuring strong advocates for both artistic mission and fiscal viability. This structure is not without risk since it requires a true partnership between the two leaders who must respect the talents and responsibilities of the other. While it would be ideal to find one individual with a perfect match of artistic vision and administrative skill, such individuals are rare. A partnership model allows the organization to benefit from the best of both worlds.

This suggestion that a new model of management be considered is not a prescription. Many opera companies, museums and other types of arts organizations will do well with one leader. Nor is it meant to suggest that administrative issues are more important than artistic concerns. Too often, when an arts institution has fiscal problems, the Board will decide that the artists are wasteful and that a strong administrator is needed to run the entire organization. The real problem in most of these organizations is not wasteful artists (some of whom do exist) but poor revenue generation capability, stemming from inadequate marketing and development activities. The problem may call for the addition of a top-level administrative leader, or for bolstering certain staff departments, but it rarely calls for the demotion of the chief artistic personnel.

Indeed in any management structure, the leadership must be supported by a strong set of functional managers. The number and size of each department will depend upon the size of the organization, what it can afford, and the complexity of its operations.

Most arts organizations have a marketing director and a development director although some institutions place both functions under the leadership of one individual (e.g., Director of Public Affairs). This logical organizational relationship is also a potentially dangerous one. Too frequently, the need for contributions is so great that the Director of Public Affairs becomes a super-development executive and the marketing function is left without a top-level advocate. In the end, this model can result in reduced marketing strength rather than the substantial interplay of marketing and development that was its objective.

The structure of the remaining staff departments depends on the organization. Whether the staff is organized by function (finance, production, etc.), by program or in some matrix structure should depend on the strategies of the institution and the most effective way to implement them. While most organizations are structured by functional area, many have specific programs that are so discrete that they benefit from separate organizational identities.

The appropriate size of each department also differs by organization. It is helpful to compare the size of one's own departments with those of peer organizations. If similar organizations have three or four development or marketing staff and your organization has only one, you are likely to be at a serious disadvantage. If you have twice the number as your peers, one must question staff productivity and cost effectiveness. How much money is raised on average by each development staff member for your organization versus your peers? What is the earned income per marketing staff? What are marketing expenditures per staff member?

Too many institutions react to financial crises by automatically reducing the size of all staff departments. If fund-raising and marketing staff are working effectively, it is counter-productive to reduce their size. In fact, it is frequently necessary to increase staff size in these departments during fiscal crises. It is hard to find situations where the addition of strong development personnel did not result in substantially more revenue than expense.

Of course, not all staff members are equally strong and every arts organization must develop a staff evaluation process of some kind. Without a personnel review program, it is difficult to ensure that all staff is being given appropriate feedback on performance, and that a proper paper trail has been established for those personnel who should be dismissed. The size and complexity of this system will vary; installing a highly structured process can frequently result in "evaluation backlash," with few personnel actively participating in the system.

Ideally, the evaluation process affects salary decisions. Better employees should be rewarded with better salaries. Yet the level of salaries in virtually every arts organization is so low, and the budget available for raises so small, that it is difficult to reward the best employees in any meaningful way. One solution is to plan multi-year raises for the best employees. If the funds are not available to give an appropriate raise this year, spread the raise over two or three years, giving the special employees an understanding of their value to the organization and the benefit to them of remaining with the organization.

Finding these special employees is exceedingly difficult, particularly for the most senior positions in an arts organization. Many institutions have turned to executive search firms to fill senior positions, others have created Board-managed search committees. In either case, a clear understanding of the needs of the institution, an important element of a carefully constructed plan, is an essential prerequisite to initiating a successful search.

Indeed the focus of all personnel and organizational planning must be on attracting the best arts administrators possible. While one can discuss planning methodologies for days, the truth is that without the right team of implementers, no plan will be effective. And a strong entrepreneurial manager, of whom there are far too few, will out-perform a poorly managed institution with a comprehensive plan. The combination of a strong plan and a strong team of managers, properly organized, is, of course, ideal.

ORGANIZATION PLANNING ISSUES

Each of the following issues should be addressed in the organizational plan for the Board:

- How can staff creativity be fostered?

- How can inter-departmental communications be maximized?

- Should the culture of the organization be changed to allow for growth?

- Does the organization have a personnel review policy?

| next |